Western Massachusetts has a lot of character—and characters.

One of the characters who have given our hilltowns a lot of character in recent years is Nan Parati. Originally from New Orleans, the artist-turned-storekeeper lives in Ashfield, where she is the proprietor of Elmer’s Store.

She was visiting a friend in Ashfield in August 2005.

“I was heading back to New Orleans,” she told me recently, “when a friend of mine called from New Orleans and said, ‘Hey, we’re about to get a big hurricane. Maybe wait until after the weekend to come back. Everyone’s evacuating.’

“So I came back to wait out the hurricane, which turned out to be Katrina, which took out my house and my studio and I said, ‘I reckon I live in Massachusetts now!’

“I had some investment money from a house I had just sold in North Carolina and used that to build Elmer’s instead of going back to rebuild in New Orleans. (I had just spent 25 years building a design business in NO and decided I didn’t want to start that all over again—I wanted to do something new!)”

Elmer’s is a general store, as it has been since 1937, but under Nan’s direction it has become a restaurant, a gallery for artists and local products, and a hub for musical events—particularly those highlighting Louisiana music.

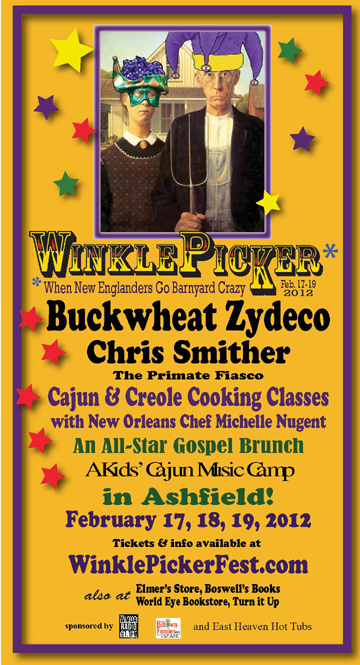

This weekend Elmer’s is hosting its first annual Winklepicker Festival. (If you want to know what a Winklepicker is in this context, just visit its web site!) The festival’s theme, for this year at any rate, is Mardi Gras. After all, this signature holiday of Nan’s native state falls next week.

The festival will feature lots of Louisiana-style music, a gospel brunch, a kids’ music camp, and Cajun and Creole cooking classes given by Nan’s New Orleans chum Michelle Nugent.

“Since I’m from New Orleans, people ALWAYS ask me about Louisiana cooking,” Nan told me. She met Chef Michelle Nugent two decades ago at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. A passionate advocate for Louisiana food, Michelle is the food coordinator for this annual April event; Nan creates the festival’s signs and serves as art co-coordinator.

I called Michelle Nugent to interview her for one of our local papers. She told me she was enthusiastic about coming to New England. “I lived in Massachusetts when I was a little bitty girl,” said the chef. “I love snow!”

She plans to offer three classes. Friday’s session will present a classic Creole dinner party, from Oysters Rockefeller to Bananas Foster. Saturday’s class will focus on a classic New Orleans-style brunch. On Sunday Michelle will explore Cajun Country cuisine.

Michelle noted that she isn’t sure what to expect in terms of an audience for her classes. “It might just be people who go to the festival to hear the music and come on a whim,” she said. “I’ve traveled enough around the country to know that people are fascinated with New Orleans and fascinated with our foodways.”

She explained that the classes are structured to help people learn more about the different types of food in Louisiana. “It seems to me that when I talk to people that aren’t from New Orleans they’re often confused about what’s Cajun, what’s Creole, what’s authentic, what’s nouvelle. And they think everything’s too hot, which isn’t usually the case.”

I asked her to elaborate a bit on the origins of Creole versus Cajun cuisine.

“Creole comes from the Spanish criollo, which means ‘born here in this place,’” she said. “In New Orleans after the Native Americans we had French and then Spanish and then French and then Spanish. And then New Orleans was a large port city and of course we had Africans come over with the slave trade, but we also had a lot of free people of color from what is now Haiti.

“So Creole could really mean a little bit of everything. It was encouraged for the French aristocrats to take Black mistresses. So we got pretty mixed up pretty fast!

“The Creole food has French aristocratic traditions and some traditions from Africa such as okra and then the use of hot pepper and things like that, which is not nearly as severe as people think it is.”

In contrast, she explained, the Cajuns were the Acadians—French refugees from Canada, with a little German blood mixed in for good measure. Michelle described their cuisine as “more countrified food.”

“It reflects the fact that these people make their living off the land with fish and shrimp and crawfish and rice,” she said.

Asked what she likes to make and eat on a daily basis, Michelle thought for a minute. “At home I just ‘pot cook,’” she noted. “I love to pot cook whether it’s beans and rice or gumbo. I find that things like that, especially gumbo, always taste better the next day. I will break my rule for these classes, but normally I make gumbo the day before and put it in the refrigerator overnight.”

It was a little harder for Michelle to identify her favorite Louisiana food in general.

“Hmm,” she mused. “Probably boiled crabs. I eat them plain. Some people eat them with saltines or cocktail sauce. I loved all boiled seafood, but crabs are my favorite.”

She sighed.

“And then there’s nothing better than an oyster po’ boy.”

Since I had only met Michelle over the phone, I asked Nan to describe her to me.

“Michelle … is wild, determined, strong, serious about what she does, fun to work with on my part and fun to stand back and watch when vendors [at the New Orleans Jazz Fest] sneak out of line,” enthused Nan.

“She loves a good time, she’s extremely smart and talented, has great taste in clothes and belt-buckles, is a wonderful, wonderful cook—and I am looking forward to spending a week with her up here!

“It’s always fun to me when New Orleanians come up here to visit because if you put New Orleans on one end of a stick and were trying to figure out where Ashfield went on that stick in relation to New Orleans, you’d have to go all the way to the very opposite end of that stick to find Ashfield. They couldn’t be further apart in way of life!”

If you’d like to enroll in this weekend’s cooking classes, call Elmer’s Store at 413-628-4003. For those who can’t make it to Ashfield Michelle has given me her recipe for a classic Louisiana dish. I made it for my family recently, and we adored it.

Modern Times Shrimp Etouffée

Courtesy of Michelle Nugent

Michelle Nugent uses the words “modern times” because, she notes, “local lore suggests that the original Acadian settlers would not have had flour or tomatoes when they first arrived in Southwest Louisiana.” She adds, “You may also substitute crawfish tails or chicken for the shrimp.”

Ingredients:

6 tablespoons butter

4 tablespoons flour

2 cups chopped yellow onions

1/2 cup chopped celery

1/2 cup chopped bell pepper (Michelle likes red for its sweetness)

4 to 6 cloves garlic, finely chopped

2 bay leaves (fresh if possible)

2 sprigs fresh thyme, leaves picked off the stem

2-1/2 to 3-1/2 cups shrimp stock (see recipe below)

1 cup tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and chopped (optional)

1-1/2 to 2 pounds fresh shrimp, peeled (save the shells for the stock recipe)

Worcestershire sauce to taste

kosher salt, freshly ground black pepper, and cayenne pepper to taste (I used 1-1/2 teaspoons salt, 8 twists of the pepper grinder, and about 1/4 teaspoon cayenne)

liquid pepper sauce (Michelle prefers Crystal®, but I used what I had in the house; I put in only 7 drops so it wouldn’t overwhelm my diners)

lemon juice to taste (I used the juice of half a large lemon)

1 bunch whole scallions, thinly sliced

1/2 bunch flat-leaf parsley, chopped

hot, cooked white rice

Instructions:

In a large heavy saucepan or cast-iron skillet heat 4 tablespoons of the butter over medium high heat and whisk in the flour. Cook this roux, stirring frequently, until it is the color of peanut butter. This is the trickiest part of the recipe since one has to watch and stir A LOT to keep the roux from burning.

Add the onions to the roux; they will darken the roux a bit further as the sugars caramelize. Stir in the celery and peppers and cook until the vegetables start to soften, about 5 minutes. Again, stir to keep everything from burning.

Add the garlic, bay leaves, and thyme. Whisk in 2-1/2 cups stock and the tomatoes if desired, and bring the mixture just to a boil. Turn the heat down to a simmer, and add more shrimp stock if the stew looks too thick. (Be careful: I added a bit too much, and the final product was a little wet although delicious.)

Add Worcestershire sauce, salt, peppers, and pepper sauce to taste. Cook for 30 minutes uncovered, stirring occasionally.

Add the shrimp to the stew and cook for 5 minutes longer. Add lemon juice to taste. Add Meat spice seasonings to taste. Stir in half of the scallions and the parsley and cook for 5 more minutes or until the shrimp is just cooked through and flavors have melded.

Finish by gently stirring in the last bit of cold butter for richness and shine. Serve with hot cooked rice. Garnish with the reserved scallions (and a little more parsley if you like), and put a bottle of pepper sauce on the table for individual adjustment.

Serves 4 to 6.

Ingredients:

the heads and shells from 1 to 2 pounds fresh shrimp

1 tablespoon butter

1 tablespoon tomato paste

3 tablespoons brandy

1 carrot, chopped

1 yellow onion with peel, roughly chopped

1 rib celery, chopped

1-1/2 quarts water

1 to 2 bay leaves

1 sprig fresh thyme

a few whole peppercorns

Instructions:

Heat the butter over a medium-high flame in a heavy-bottomed saucepan. Add the shrimp shells and sauté until they start to brown; then add the tomato paste and the vegetables and sauté until brown. Carefully add the brandy and then add the water and the seasonings. Bring the liquid to a boil and then simmer for 20 to 30 minutes.

Strain the stock, discarding the solids, and set it aside to cool.