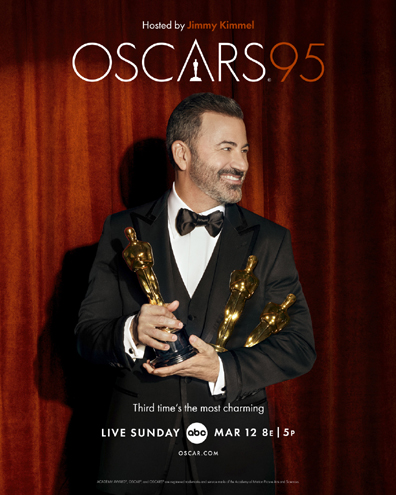

THE OSCARS® – Key Art. (ABC)

Those of you who know my academic background and my personal proclivities are aware that I am a pop-culture person. In honor of Sunday’s Academy Awards, I’m going to talk about my favorite nominated film. It seems to be almost everyone’s favorite … and for good reason.

Everything Everywhere All at Once is messy and complicated, but as anyone who has ever visited my house can tell you, I’m a firm believer that mess and complexity breed creativity.

The film’s Chinese-immigrant heroine, Evelyn, starts out middle aged and miserable. Her family and her business are in crisis. Domestic drama morphs into science fiction (and numerous other genres) when Evelyn discovers that she inhabits not just the world she knows but a multiverse … and that she alone of all the beings in that multiverse can save it from annihilation.

Along with her quiet husband, her rebellious daughter, and her disapproving father, she leaps through time and space. In her quest to rescue the cosmos, she inhabits several alternative versions of herself. She is a glamorous movie star with martial-arts training, like Michelle Yeoh, who plays her. She is a lesbian in a world where humans have hot dogs for fingers. She is a rock on a barren mountain and can only communicate telepathically.

Photo credit: Allyson Riggs

Evelyn’s infinite lives and personas can teach her, and us, an infinite number of lessons. I’ll share two here. First, the film reminds us that life doesn’t end with youth. At the beginning, Evelyn looks and feels defeated. She becomes a warrior.

I myself am approaching middle age. I have been approaching it for years and plan never actually to enter it. Still, I am old enough to appreciate the film’s message that humans can grow emotionally and physically at any age.

I find the film’s final lesson even more powerful. The editing is dizzying as Evelyn makes rapid shifts from universe to universe to universe. And then, suddenly, near the end, the film slows down. In the middle of a fight scene, Evelyn’s gentle husband freezes the action to ask everyone to STOP. “The only thing I do know is that we have to be kind,” he pleads.

Like Evelyn and her family, if less dramatically, we can all inhabit many different versions of ourselves. We will be the best version if we follow this film’s ultimate lesson. The bravest course of action, it demonstrates, is often not battle. It’s forgiveness. Evelyn learns what prophets and songwriters have long told us: “What the world needs now is love.” I have a feeling that’s true in any universe.

Happily for me, there are a couple of food connections in this film.

The family begins the film getting ready for a Lunar New Year party. Unfortunately, the only food on hand is a pot of blah-looking noodles with some greenery stirred in.

I’m not into blah so I’m going with the hot-dog connection I mentioned earlier. The hot-dog fingers were such a hit with fans of the film that one can purchase hot-dog gloves to wear while watching Everything Everywhere All at Once. I won’t go that far, but I hope to serve hot dogs at my soiree on Sunday.

To make them more interesting (and to create an actual recipe to share with readers), I have decided to make chili dogs. Like the film, this dish is quite messy but ultimately satisfying.

Everything Everywhere Chili Dogs

I usually make chili with lots of beans, but when I was in graduate school my friend Shannon informed me that the protein in chili-dog chili should always be beef and only beef. So that is what I use here.

Ingredients:

for the chili:

1 splash olive oil

1 medium onion, finely chopped

1 large clove garlic, minced

1 pound lean ground beef

1 tablespoon chili powder

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1/2 teaspoon chipotle powder (if you don’t have chipotle, use another dried pepper, but I love the slight smokiness of the chipotle)

3/4 teaspoon salt

ground pepper to taste

1 can (14.5 ounces) crushed tomatoes

1 cup water

for the chili dogs:

6 hot dogs (I prefer all beef)

6 hot dog rolls

the chili

grated sharp cheddar cheese to taste

Instructions:

Begin by making the chili. Heat the oil in a skillet. Add the onion, and sauté for a few minutes until it smells lovely and starts to brown. Add the garlic and sauté again briefly.

Add the beef, breaking it up into small pieces as you stir and brown it. When the beef has browned, stir in the spices, the salt, and the pepper, followed by the tomatoes and the water.

Bring the mixture to a boil; then turn it down and simmer it for 30 to 40 minutes, until the flavors blend and the liquid has mostly, but not completely, boiled off. Taste and adjust the seasonings.

Cook the hot dogs in your preferred method, boiling or grilling. While the hot dogs are heating up, lightly toast the hot-dog rolls.

Onto each roll place a hot dog. Partially slicing the dogs lengthwise makes it easier to add toppings: a generous helping of chili and some of the cheese. Serves 6 Academy-Award guests. This recipe may be multiplied.

Photo Credit: Allyson Riggs