This month I feature a dish that was frequently made by a woman who would have called it a “homely receipt.” American novelist Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) used what are now archaic definitions of both words.

“Homely,” which now generally means unattractive, was then interpreted as homey or simple. And “receipt” was the 19th-century term for what we now call a recipe.

I have been a fan of Alcott since I first read “Little Women” when I was eight. Hooked, I went on to read most of her other books for young readers: “Little Men,” “Eight Cousins,” “An Old-Fashioned Girl,” “Jack and Jill,” and so forth.

When I was an adult a number of the sensational tales she wrote under pseudonyms were discovered by scholars. I was lucky enough to be able to review some of them.

At that time, I also discovered one of my favorite Alcott books, “Work.” Published in 1873, this novel for adults tells the story of a young woman named Christie who has been brought up by her uncle and aunt.

She is welcome to remain in their house when she turns 21, and she has a reliable (if not exciting) local suitor. Nevertheless, she decides to leave home and make her own living. “Aunt Betsey,” she announces, “there’s going to be a new Declaration of Independence.”

Christie wants to escape from the feeling of being a burden to others, but even more than that she wants to strike out on her own. She is excited by the prospect of exploring a world larger than the small town in which she has grown up.

She embarks on a series of jobs that reflect the occupations available to middle-class white women in 19th-century America—among them domestic servant, actress, governess, companion, seamstress, and nurse.

Some of these jobs are depressing in the extreme, particularly her work as a servant to a woman who denies Christie not just autonomy but also the use of her own name. The woman makes Christie answer to “Jane” because that is what this rigid employer is accustomed to calling her maids.

Alcott herself worked at all of the jobs in the book at one point or another. She was the main breadwinner for her family, in part because she believed, like her heroine Christie, that women could find fulfillment in work. She also sought work outside the home because her father was a terrible provider.

Bronson Alcott was a Transcendentalist educator and philosopher. An idealist, he would never take a job if it interfered with his principles. He took this admirable quality to extremes that made life difficult for his family. The Alcotts often had trouble finding enough to eat and paying their rent.

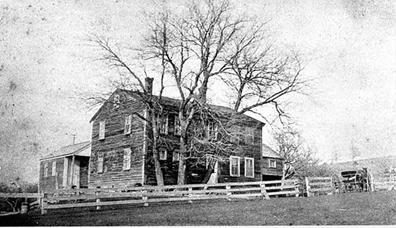

Those of us in Massachusetts can go to the town of Harvard and visit Bronson’s most disastrous experiment in living according to his principles, Fruitlands, now a museum.

In 1843 he and a number of like-minded friends decided to try to create their own Utopian community. One of the friends, Charles Lane, was wealthy. Lane purchased a home and land, and the group moved in. They called their new home Fruitlands.

The residents of Fruitlands didn’t believe in hiring labor so they intended to engage in subsistence farming. Unfortunately, few of them knew much about farming. Most of them spent more time discussing philosophy and religion or trying to find new residents for the place than trying to grow food on the land.

They drank only water, used no products from slavery or animals (they dressed in homemade linen garments and canvas shoes, which offered little protection as the temperature fell), and practiced sexual abstinence.

Although technically the group endorsed gender equality, women ended up doing most of the work. Abigail Alcott, Bronson’s wife and 10-year-old Louisa’s mother, was the lone woman at Fruitlands after the only other adult female, a teacher, was expelled for breaking down and eating a piece of fish.

Abigail was supposedly once asked by a visitor whether there were any beasts of burden on the farm. “Only one woman!” was her reply.

The Alcotts abandoned the venture in the cold, hungry month of January 1844.

Their life didn’t become financially stable until Louisa’s books began to make money a couple of decades later. Bronson managed to eke out a living of sorts until then through odd jobs and handouts from relatives and friends like Ralph Waldo Emerson.

What does this have to do with food? In 1873 Louisa penned a tale called “Transcendental Wild Oats” about a family engaged in a Utopian experiment like Fruitlands. In fact, the aspirational community in the story is also called Fruitlands.

At the end of the story, after the family has abandoned its temporary home just as the Alcotts did, the patriarch sighs, “Poor Fruitlands! The name was as great a failure as the rest!”

In a “half-tender, half-satirical tone,” his wise wife replies, “Don’t you think Apple Slump would be a better name for it, dear!”

Apple Slump was the name of a favorite dessert in the Alcott home. It’s a simple dish perfect for this season of year when apples are everywhere. As its name might suggest, it’s not precisely exciting looking. Nevertheless, it’s tasty. It resembles a cobbler with nuts added.

It would never have been served at Fruitlands as it contains milk, egg, and sugar. Nevertheless, it was frequently served at the Alcotts’ future home in Concord, Orchard House. In fact, Louisa Alcott often referred to Orchard House as Apple Slump. The recipe below comes from the Concord Museum.

Louisa May Alcott’s Apple Slump

Ingredients:

for the Apple Base:

6 pared, cored, and sliced tart apples (or whatever apples you have)

the juice of 1/2 lemon

1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract

1/2 cup firmly packed light brown sugar

1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

1/2 teaspoon cinnamon (I love cinnamon with apples so I added a little more)

1/4 teaspoon salt

for the Slumpy Topping:

1-1/2 cups flour

1/3 cup sugar

2 teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 egg, beaten

1/2 cup milk

6 tablespoons butter, melted and cooled a bit

1/2 cup chopped walnuts

Instructions:

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Grease a 9-by-13-inch baking dish.

First, make the apple base. In a large bowl, gently mix the apple slices, the lemon juice, and the vanilla. In a small bowl, combine the brown sugar, the spices, and the salt. Add the sugar mixture to the apple mixture and toss to coat it. Spread the apple base evenly in the pan and bake until it is soft, about 20 minutes.

While the apples are baking make the topping. Sift together the flour, the sugar, the baking powder, and the salt. Blend the egg and the milk together with a fork; then stir in the melted butter. Add this mixture to the dry ingredients, and stir gently.

Pour the flour mixture over the baked apples, doing your best to spread it evenly. Sprinkle the walnuts on top. Continue baking for 25 minutes, or until the top is brown and crusty. Cool for 5 minutes. The Concord Museum recommends serving it with your favorite ice cream. (I served it with caramel sauce.) Serves 6.