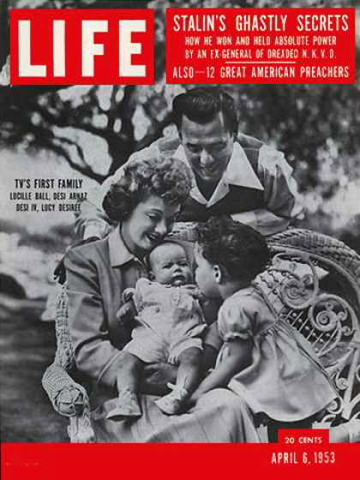

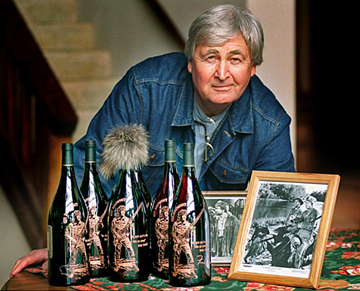

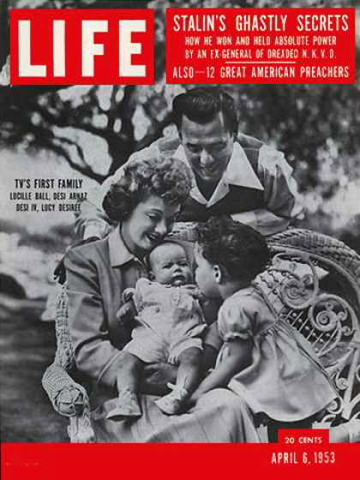

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz on the set in 1953 (Courtesy of UCLA Library)

Fifty years ago today Americans said goodbye to I Love Lucy.

The program in its half-hour format had actually been off the air for three years in 1960. The original I Love Lucy premiered in 1951 and concluded in 1957.

The production company owned by Lucy’s stars and creators, Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, went on to produce several hour-long episodes of the program. Desilu’s Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour aired sporadically between 1957 and 1960. The finale was broadcast on April 1, 1960.

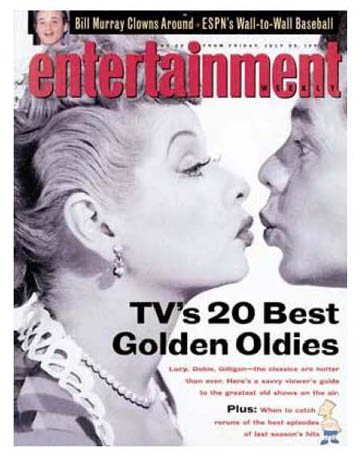

I Love Lucy was no ordinary television show. This popular, groundbreaking program helped establish the technical norms and conventions of the situation comedy.

In addition, it fit into and further refined the subject matter of the sitcom—marriage and family life.

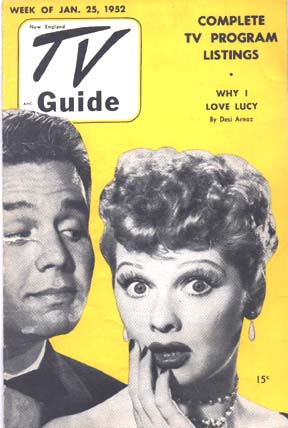

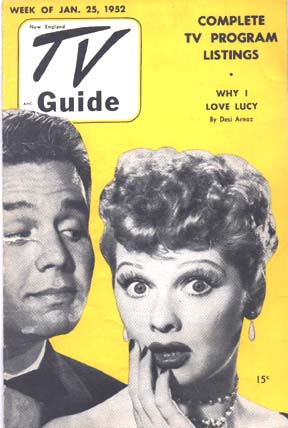

As just about anyone who has ever watched television knows, Lucille Ball played Lucy Ricardo, a madcap housewife who schemes in episode after episode to escape from her apartment and move onto a larger stage—often a literal stage; she has aspirations to a career in show business.

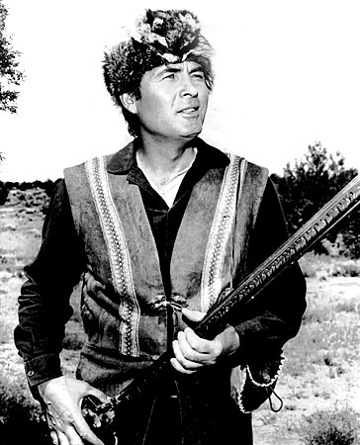

Desi Arnaz played Lucy’s husband Ricky. A Cuban-born bandleader and singer like Arnaz himself, Ricky frequently bursts into Spanish tirades. His main function in the storyline is to depress Lucy’s ambitions and reinstate her in their home.

The love of the program’s title bridges the gap between the motivations of Lucy and Ricky. Many episodes end with a kiss.

In a sense, the series is a televised version of Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique, illustrating the ways in which women in the 1950s were encouraged by their husbands and by society at large to see the home as their natural domain.

It doesn’t take a Freudian (or a Friedanian) to see symbolism in the giant loaf of bread that pins Lucy to the kitchen wall in the episode “Pioneer Women.”

Of course, the show’s viewers were never meant to see this comedy as a critique of societal norms. The producers and stars saw the war between the sexes as eternal fodder for humor.

I Love Lucy’s presentation of marriage was complicated by the fact that viewers in the 1950s were aware that Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz were married in real life. The often told story of their offscreen marriage supported and enriched the story they enacted each week onscreen.

In interview after interview, Ball told the press about the difficulties the two had encountered—their contrasting cultural backgrounds, their conflicting work schedules, their struggle to have children.

She presented I Love Lucy as the salvation of the Arnaz marriage. Ball explained that she worked so hard, played this character, mainly in order to be a good wife.

The ties between the Ricardos and the Arnazes reached their pinnacle in January 1953 when the real Ball and the fictional Lucy gave birth to boys on the same day.

Despite the success of Desilu and I Love Lucy, the Ball-Arnaz marriage foundered as the decade wore on.

The Arnaz family business grew into a giant, and the Arnaz family was together more onscreen than anywhere else. Desi Arnaz drank and carried on with other women. Lucille Ball became bitter. Eventually the program that had cemented the marriage began to show cracks in that cement.

Watching the final episode of The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour, “Lucy Meets the Moustache,” one can see the signs of strain.

Arnaz looks portly and grim. Ball looks stiff and grimmer. They are hardly ever in a shot together, and the male-female sparring appears harsh rather than light hearted.

The program’s guest star, comedian Ernie Kovacs, has very little to do. His wife, actress/comedienne Edie Adams, sings a song that must have rubbed salt into Ball and Arnaz’s marital wounds.

The Alan Brandt/Bob Haymes tune “That’s All” begins “I can only give you love that lasts forever/And a promise to be near each time you call” and ends with the repeated statement “That’s all.” Adams’s understated singing style renders the song particularly poignant.

The kiss that ends “Lucy Meets the Moustache” is combative rather than affectionate.

Ball filed for divorce the day after shooting for this episode concluded. She went on to star in several additional situation comedies, in each playing a version of the ditzy Lucy character established in I Love Lucy.

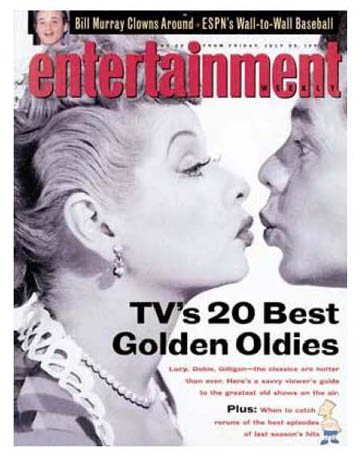

In general Americans moved on with Ball, although her first series remained her most successful one. It has never been out of syndication.

Arnaz produced a few other television shows and acted on occasion. His alcoholism took its toll, however, and he looked and acted old before his time. He died in 1986. Ball followed in 1989.

Both Ball and Arnaz had remarried in the early 1960s. Strangely, however, since their deaths they have been increasingly reunited.

A TV movie in 1991 told their story from their meeting in 1940 until the premiere of I Love Lucy. A televised “home movie” project in 1993 and the 50th anniversary I Love Lucy special in 2001 were put together by their children, Lucie Arnaz and Desi Jr.

Those same children—particularly “Little Lucie” as she was called—eventually established the Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz Center in Ball’s hometown of Jamestown, New York. It includes a museum dedicated to the “First Couple of Comedy” as well as a Desilu Playhouse that displays sets from I Love Lucy.

I’m ambivalent about the presentation of Lucy and Desi as a continuing romantic couple. Positioning them as eternal lovers implies that enduring romance stems mostly from the attraction of opposites. Love is that, but it is much more.

Nevertheless, I grew up watching I Love Lucy while knowing that the two main characters onscreen were married in real life. Like most Americans in the 1950s and today I have absorbed the story, true or not (and I see no reason to believe that it didn’t hold at least some truth), that the Arnazes’ offscreen relationship enhanced the Ricardos’ onscreen marriage.

I’m a sucker in particular for the episode in which Lucy tells Ricky that she is pregnant. In it Ball and Arnaz look young, happy, and vulnerable. It’s hard to believe that all that emotion was just acting.

And it’s even harder not to see their breakup as tragic for them and for American television.

To those of us who watched and watch, one line in Desi Arnaz’s autobiography continues to sound as genuine as an actor’s recollections ever do:

“’I Love Lucy’ was never just a title.”

Desi Arnaz was proud of his Cuban heritage so I chose to make a Cuban Sandwich for this post (also known as a Cubano or a Mixto (mixed) Sandwich.

The sandwich originated among cigar workers in Cuba and Florida. In the city of Tampa, where Cuban immigrants were joined by Italians, salami is included in the sandwich. Elsewhere the ingredients are roast pork, ham, Swiss cheese, mustard, and butter, all served on Cuban bread.

If you can’t find Cuban bread (I couldn’t when I set out to make this sandwich), use a French or Italian loaf; the bread should be a bit crusty on the outside but soft on the inside. A traditional baguette will be too thin and crispy.

To me the most flavorful ingredient is the pork so I roasted my own pork. Purists would probably bake their own ham with a sweet glaze, but I chose to purchase a high-quality honey ham.

The recipe below substitutes American cheddar for the traditional Swiss cheese in Lucy’s honor to make a Cuban-American sandwich. If you prefer to be authentic and use Swiss cheese, you will still be able to say you honored this actress with the ham!

A Cuban Sandwich is traditionally pressed together with a press called a plancha. If you have a Panini press, use that. My family and I employed a George Foreman grill. If you have no press of any sort, use a griddle to heat your sandwiches, and warm a cast-iron skillet. You may press down on the top of the sandwiches with the bottom of the hot skillet.

The quantities for the sandwich ingredients are really just suggestions. We used a bit less of everything (except the bread!) than I have required here. See what tastes good to you….

For the Pork Roast (cook this the day before you want to make your sandwiches):

Ingredients:

1 small onion, finely chopped

4 cloves garlic, finely chopped

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground pepper

3/4 teaspoon oregano

3/4 teaspoon cumin

1/2 cup key-lime juice

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

1 pound pork tenderloin

a small amount of additional extra-virgin olive oil for heating the pork

Instructions:

In a mortar and pestle push together the onion, garlic, salt, pepper, oregano, and cumin. Whisk them into the key-lime juice and set the mixture aside.

In a small saucepan heat the 1/4 cup of olive oil until it shimmers. Whisk in the citrus mixture, and remove the pan from the heat. Allow it to cool to room temperature.

Combine the pork and the marinade in a plastic bag, and allow the pork to marinate for 1 to 2 hours. About 15 minutes before you want to finish the marinating process, preheat the oven to 425 degrees.

In an ovenproof skillet heat a tablespoon or two of olive oil. Remove the pork from the marinade (but save the marinade), and brown it as well as you can on all sides. (This won’t be easy because it has been marinated, but you should be able to get some color.)

Pour the marinade over the pork, and place the skillet in the preheated oven. Roast the pork for 20 minutes. Remove it from the oven, and put an aluminum-foil tent over it. Let it rest for 1/2 hour; then cool it to room temperature and chill it overnight so that it will be easy to slice the next day.

For the Sandwiches:

Ingredients:

enough Cuban bread for 8 sandwiches, cut into 8 pieces about 6-inches long each (I used long Italian rolls) and sliced in half lengthwise

butter as needed

yellow mustard to taste

1 pound roasted pork tenderloin (see above), cut into very thin slices, plus a little of its juice

thinly sliced dill pickles to taste

3/4 pound sliced ham (homemade or good quality)

1/2 pound thinly sliced Wisconsin or Vermont cheddar (for Lucy) or Swiss (for Desi) cheese

Instructions:

Butter both inside sides of the bread, and put mustard on one side. Drizzle a little of the pork juice on one side as well.

Assemble your sandwiches in this order from bottom to top: pickles, pork, ham, cheese. Put the two halves of the sandwiches together.

Heat your pan or grill. Place the sandwiches on it, and press down on them firmly with another surface (the top of your press or another hot pan). Heat until the sandwiches are depressed and the cheese is melted.

Serves 8 generously.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider taking out an email subscription to my blog. Just click on the link below!

Subscribe to In Our Grandmothers’ Kitchens by Email.